Introduction

Archaeology in general, and archaeology field schools in particular, faced significant headwinds even before Covid came to the fore in mid-2020. Few academic jobs, pressure on universities to show Return on Investment (ROI) for student’s tuition payment, and the increased cost of higher education were all forces impacting archaeology. Since Covid, and in many cases because of the pressures and political outcomes it brought, archaeology is changing at an accelerated rate. The number of open tenure academic positions today is extremely small, students are moving away from majoring in social sciences and humanities, and the world is getting more dangerous by the day. At the same time, the 2021 Federal Infrastructure Investment & Jobs Act, other federal funding streams and general global climate conditions are creating huge demand for Cultural Resource Management professionals (Fig 1). How are all these forces impacting archaeology field schools?

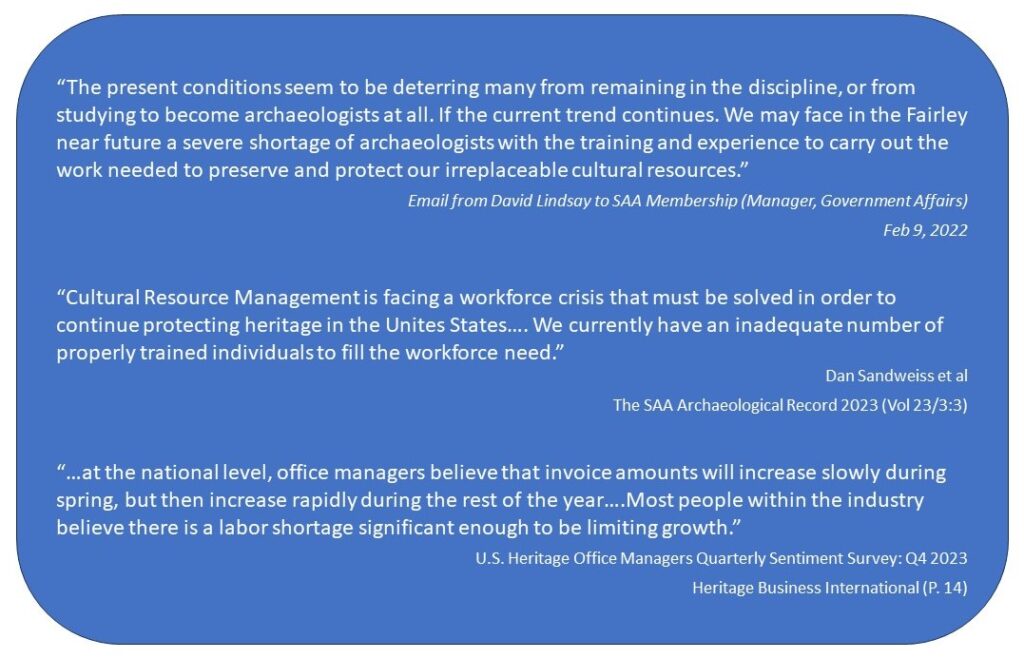

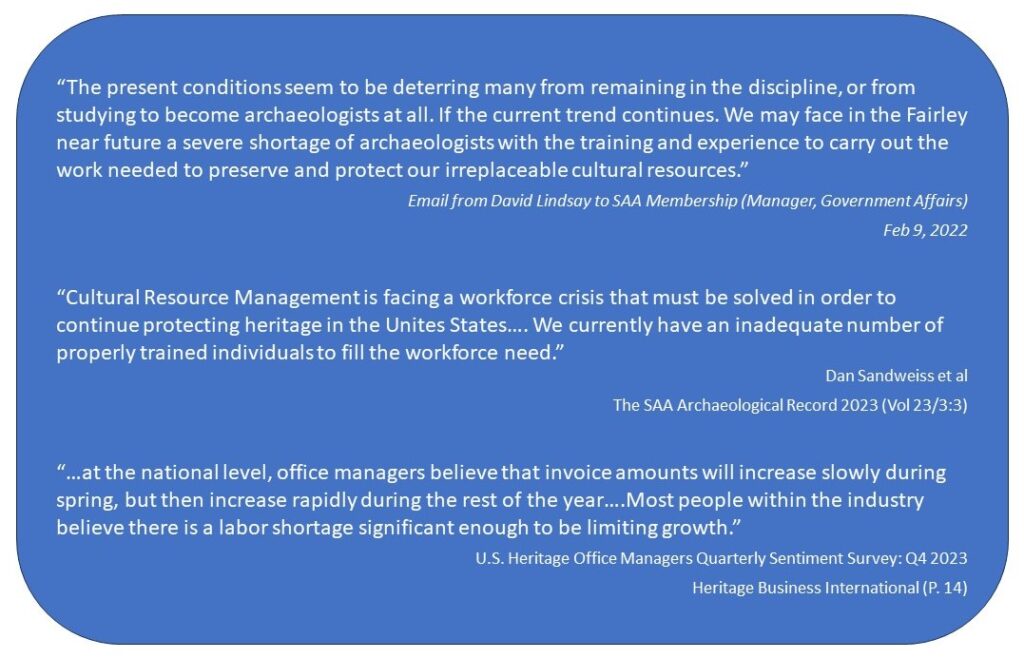

Figure 1: Citations from leading scholars regarding the current state of archaeology & CRM

In the following text, I will present data and insights that impact archaeology field schools, writ large. While I have been involved with hundreds of field schools in the past 30 years, we are on new, post-Covid grounds. Past patterns and trends are no longer relevant and new, powerful forces are pushing archaeology in new directions.

General Geopolitical Background

According to The Economist, 2024 will be the biggest election year in history. More than half of the world’s population will be voting in 2024, mostly in polarized political and social environments. Young people of all political stripes would likely take significant part in these elections and divert interest from almost everything else towards the political future of their communities. Due to the polarized political environment, Josh Zumbrum – a Wall Street Journal columnist specializing in the study of numbers – believe that data quality is getting worse when we might need the numbers most. We must be careful how we collect and interpret data.

The war in the Ukraine is going into a stalemate, and the one in the Middle East is in significant danger of spreading beyond the Israel-Hamas conflict. It may still draw the US into a regional conflict. China is unpredictable, and Xi’s announcement that China will surely unified with Taiwan at his New Year address and the election in Taiwan of the pro-independence Lai Ching-te suggest that a super-power armed conflict in the East China Sea may go kinetic. These global, geo-political tensions have a direct, and adverse impact on our ability to run – and attract students – to archaeology field schools, especially outside North America.

Finally, the attractive power of college education in the U.S. is losing its luster. Between 1965 and 2011, university enrollment increased nearly fourfold to 21 million as the earning differential between high school and college graduates expanded. In the past decade, American’s confidence in higher education fell from 57% to 36%, according to a July 11 Gallup Poll. Nearly half of parents say they would prefer not to send their children to a four-year college after high school, even if there were no obstacles, financial or otherwise. Two-thirds of high-school students think they will be just fine without a college degree.

These geopolitical and economic forces are forcing universities, faculty, industry and politicians into a serious rethink of higher education. But these forces are also already impacting individual student choices. And some data is emerging, showing trends and patterns.

Relevant Field School Data & Analysis

To understand trends within archaeology, I begin by reviewing data from databases looking at U.S. Study Abroad patterns, known as the annual Open Doors report – published annually by the IIE. I will then analyze data collected by the Twin Cairns Intelligence Unit about archaeology field schools as harvested from various websites – but primarily from the AIA site. I will then explore data collected by the Center for Field Sciences, reflecting the operation of a large archaeology field school provider.

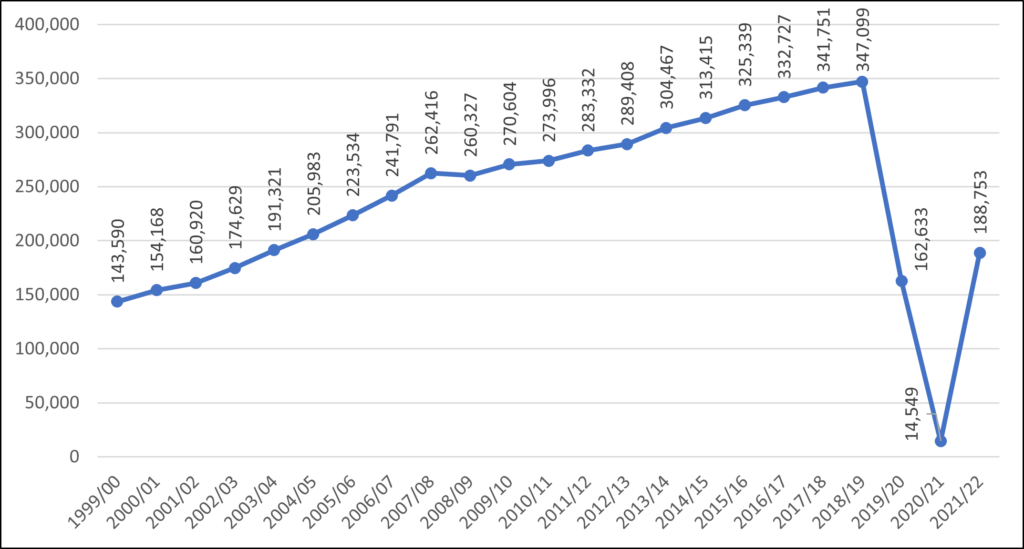

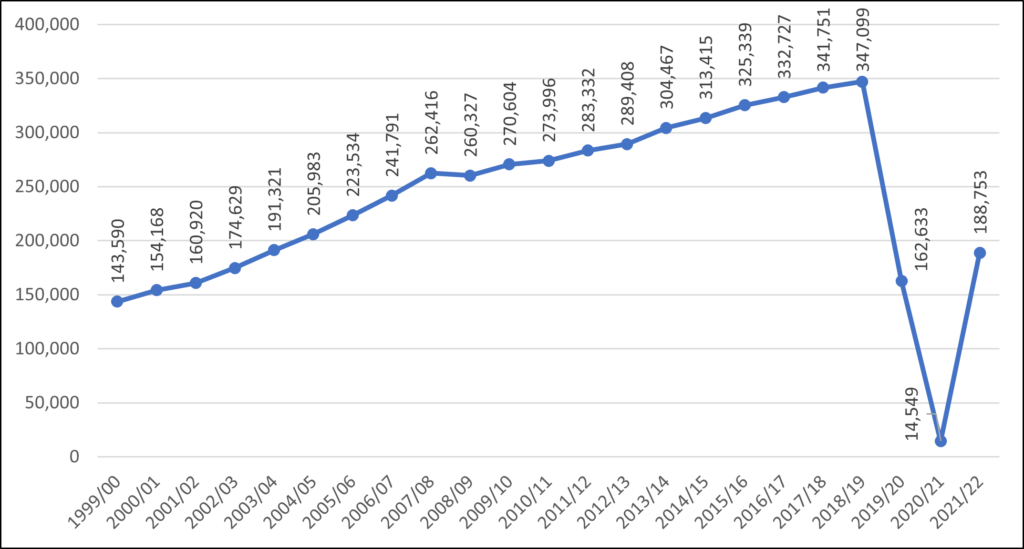

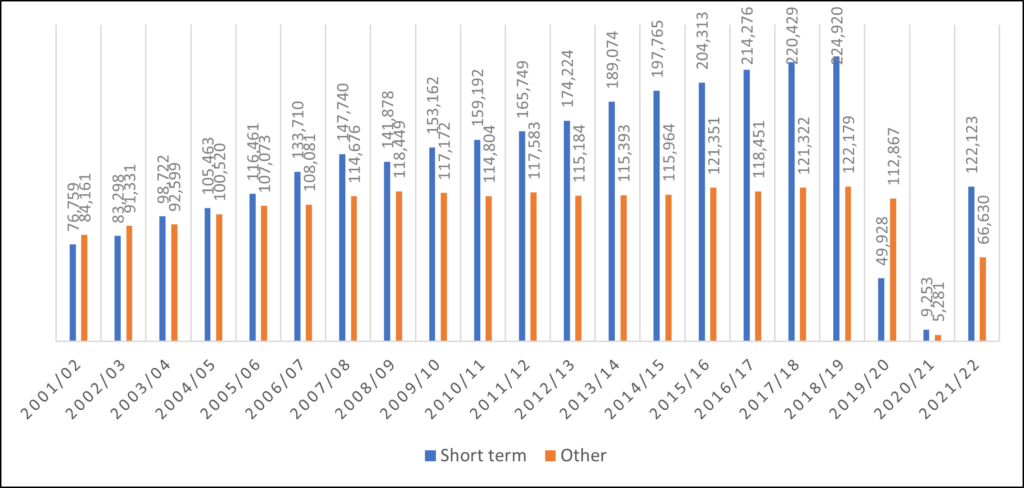

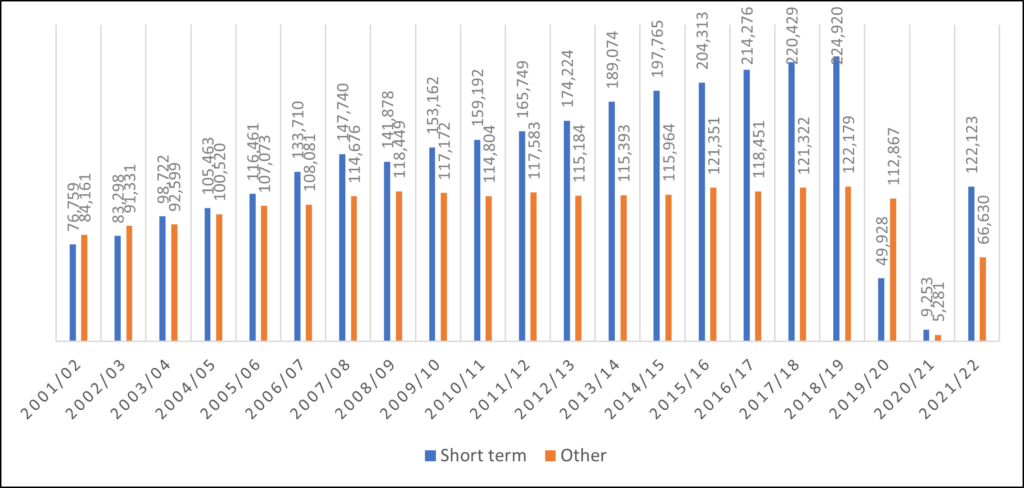

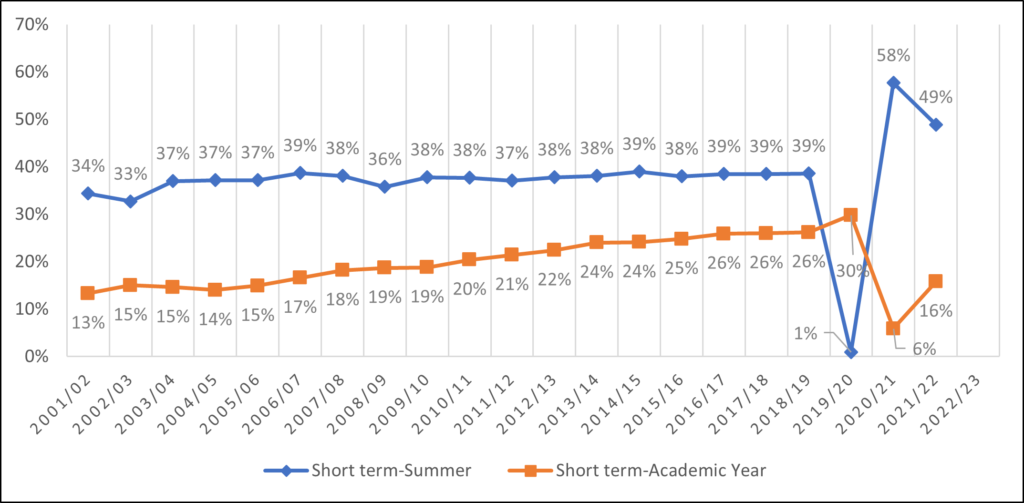

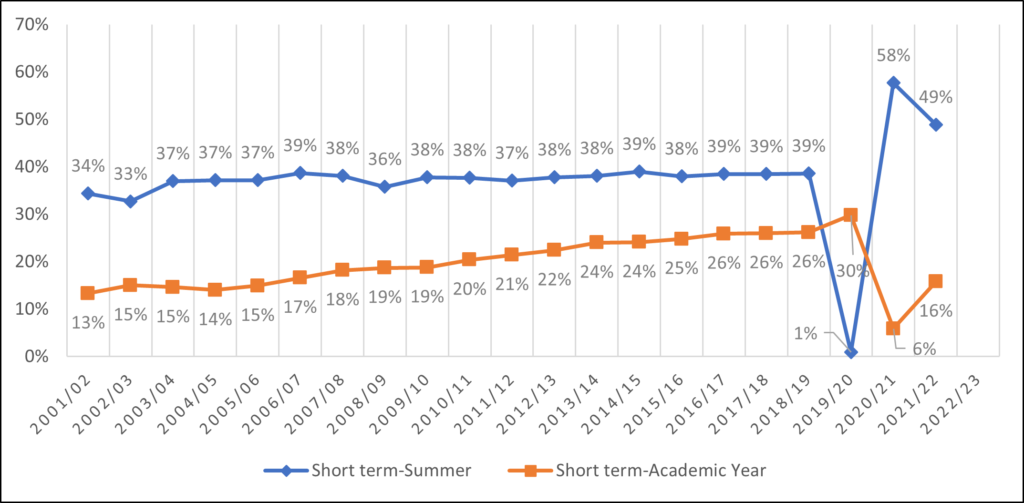

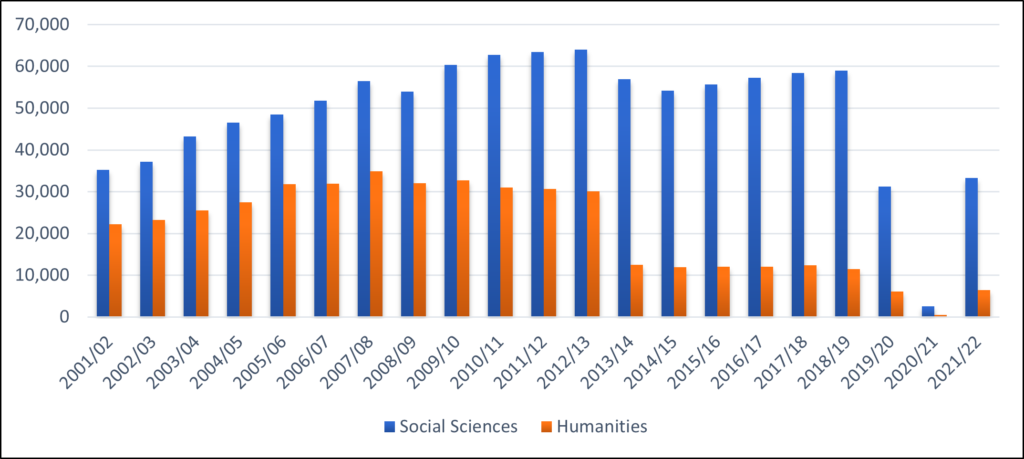

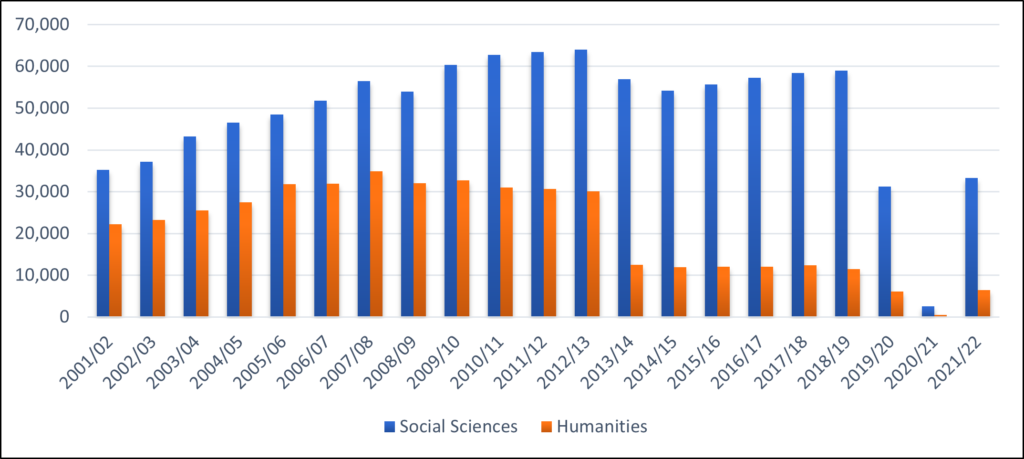

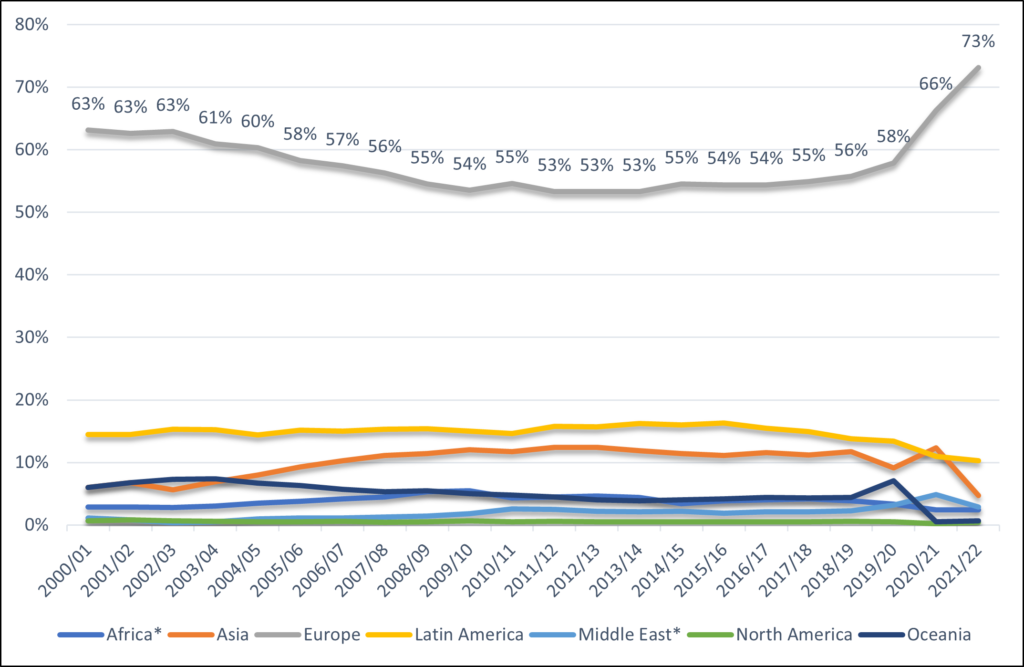

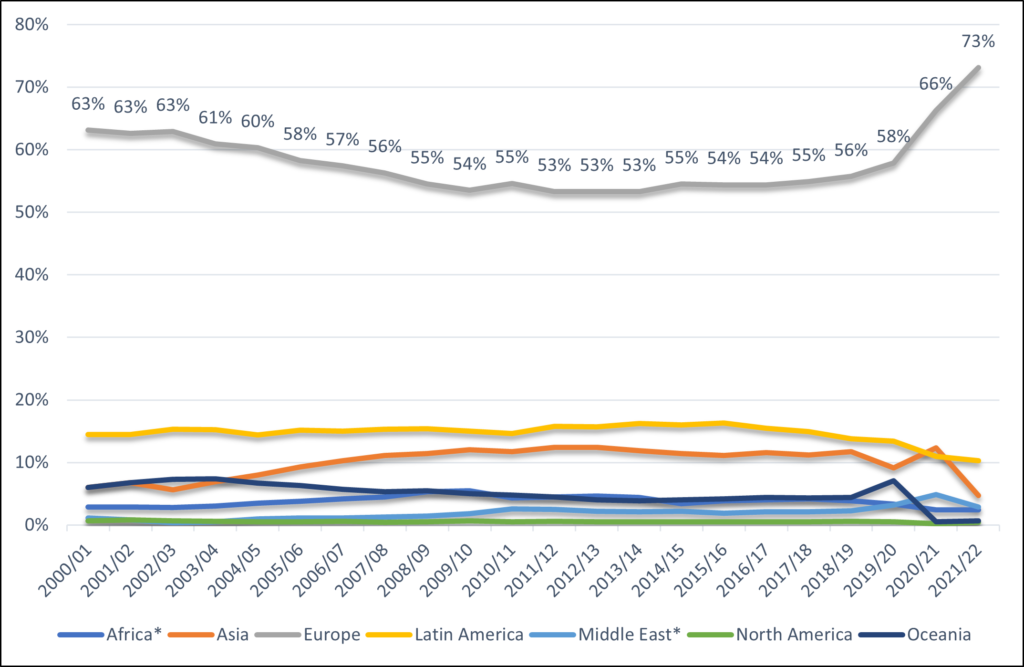

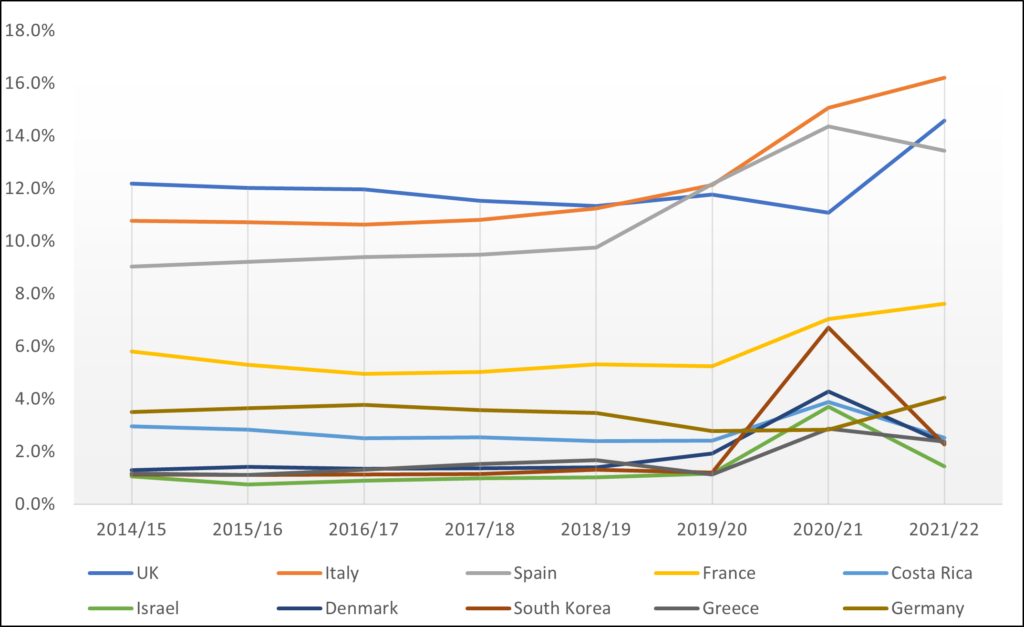

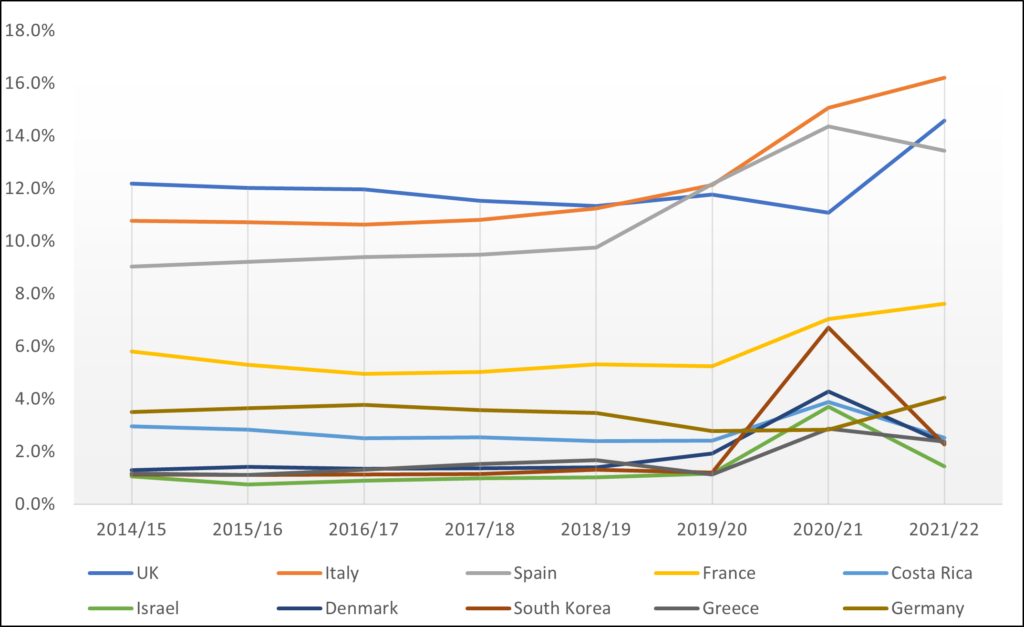

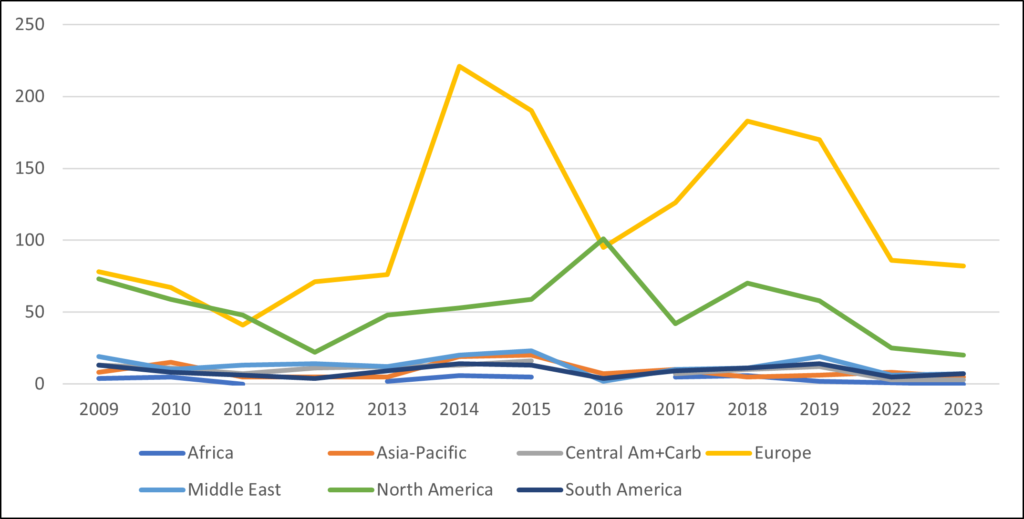

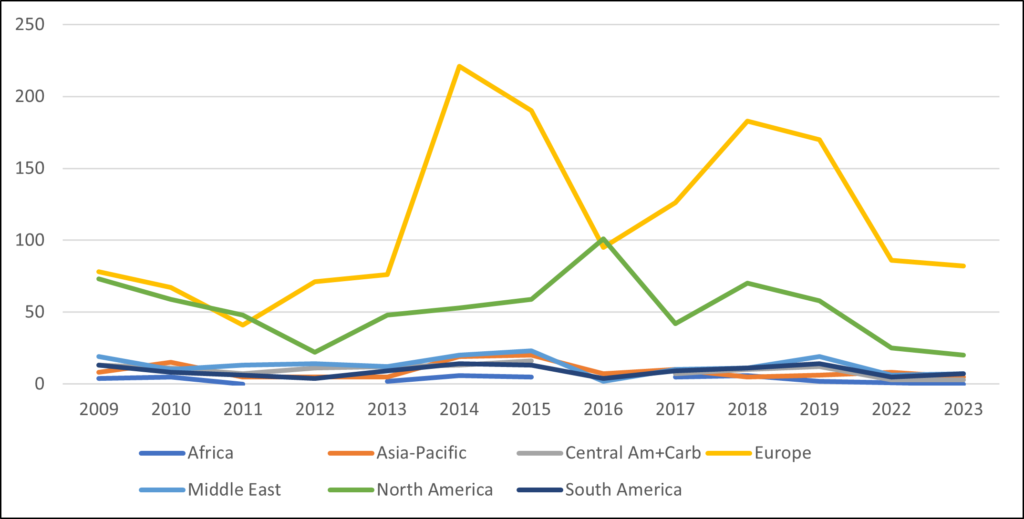

The number of US students participating in Study Abroad programs recovered somewhat last year, but has not yet reached pre-Covid numbers (Fig. 2). Student choice is shifting from quarter/semester abroad to intensive, short term programs, primarily during the summer (Fig 3-4). The number of students from the Social Sciences and Humanities who study abroad declined – like all other disciplines – but returned to good strength last year (Fig 5). Students are much more risk averse and are choosing to travel to Europe as their Study Abroad preferred destination (Fig 6). Italy, the UK and Spain being the most favorite destinations, attracting 44% of all Study Abroad students last year (Fig 7).

Figure 2: Number of Study Abroad students by year (Data from the Open Doors annual report)

Figure 3: Number of US students attending Study-Abroad programs, comparing short term (8 or less weeks) for quarter or semester abroad (Data from the Open Doors annual report)

Figure 4: Comparison of percentage of students attending short term programs between summer vs, programs running during the academic year (Data from the Open Doors annual report)

Figure 5: Number of students from Social Sciences and Humanities attending Study Abroad programs – archaeology is the US is taught under anthropology, a social sciences discipline r (Data from the Open Doors annual report)

Figure 6: Host regions for US Study Abroad programs (Data from the Open Doors annual report)

Figure 7: Top 10 Study Abroad destination countries (Data from the Open Doors annual report)

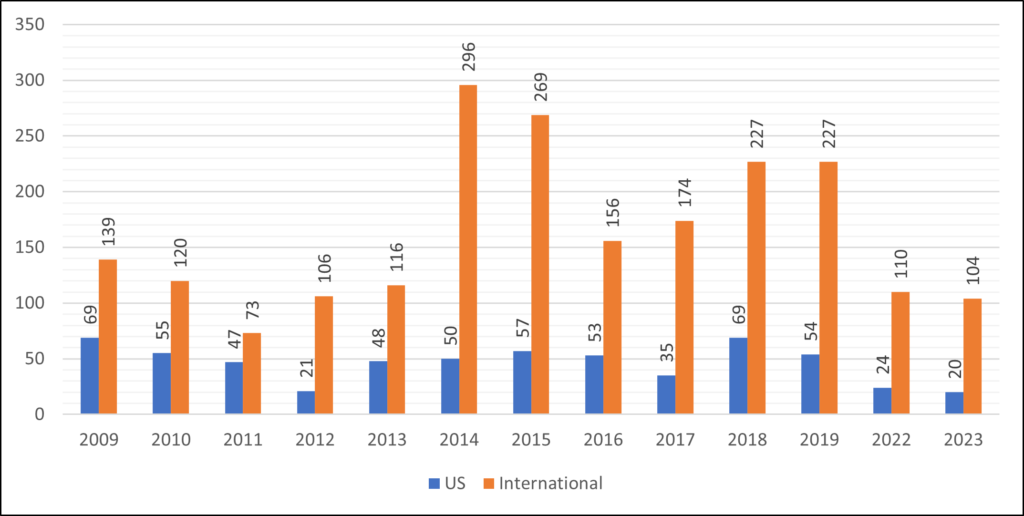

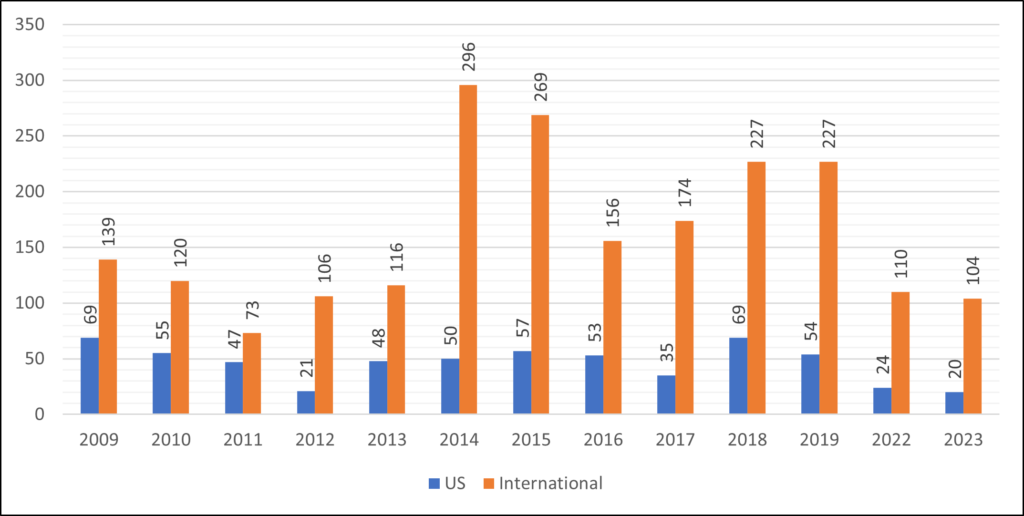

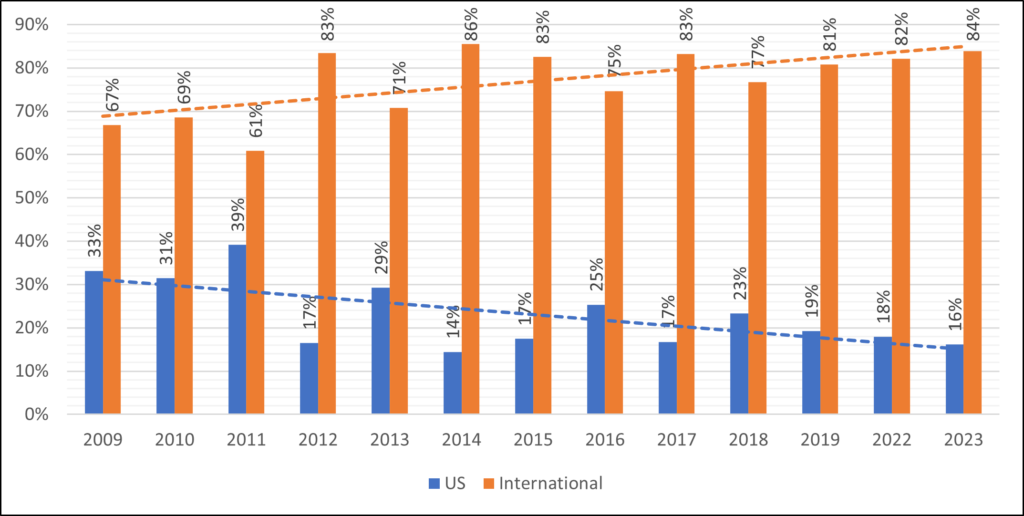

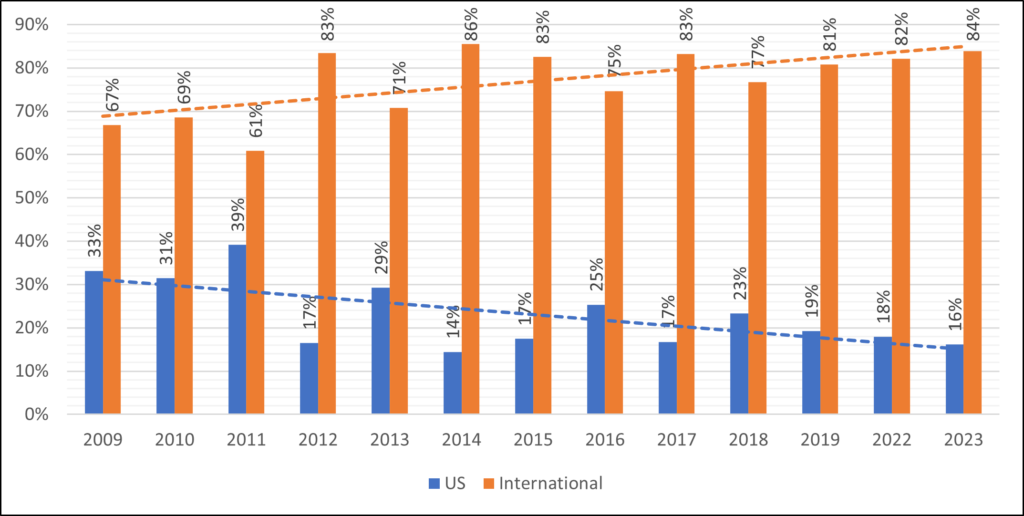

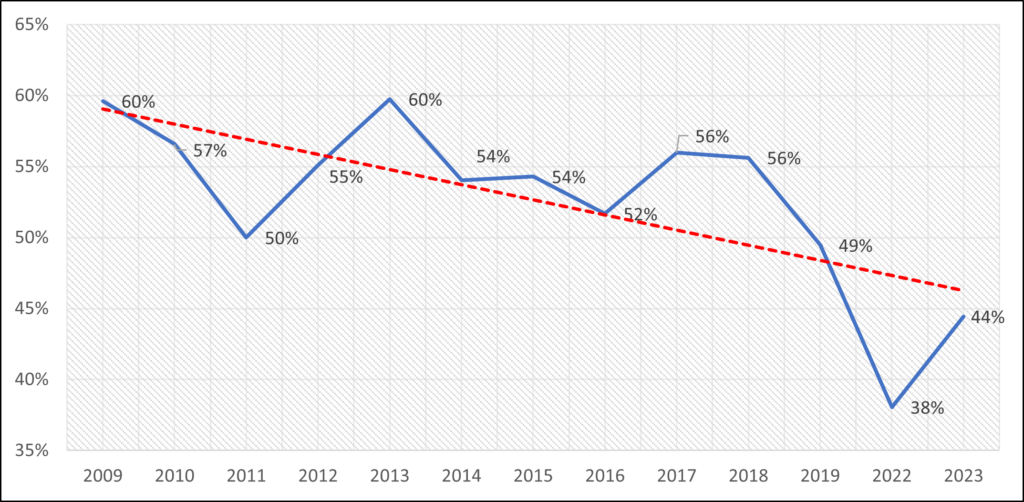

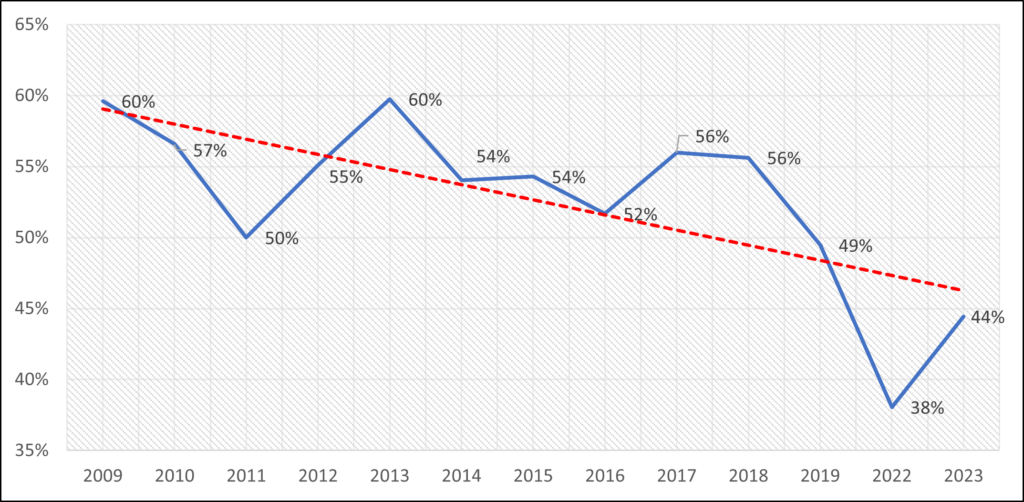

Reflecting the general Study Abroad data, archaeology field schools have been traditionally concentrated in Europe (Fig 8). Despite the lack of academic positions and the great demand for CRM professionals in the post-Covid era, academic archaeologists moved even further into offering international field schools (Fig 8). By 2023, the number of domestic U.S. programs that can best train students for CRM careers declined to the lowest level ever recorded, only 20 such programs were offered (Fig 9-10). Initial numbers for 2024 are not encouraging, and thus far there are only 18 domestic programs posted on the AIA fieldwork site.

Figure 8: Number of field schools by continent (Data from the Twin Cairns Intelligence Unit)

Figure 9: Number of domestic (U.S.) vs. international field schools (Data from the Twin Cairns Intelligence Unit)

Figure 10: Percentage of domestic (U.S.) vs. international field schools (Data from the Twin Cairns Intelligence Unit)

To save costs and compete over the shrinking student pool, fewer field schools are offering academic credit units (Fig 11). More field school directors are going it alone, providing no umbrella coverage and no insurance, liability, student health care or any type of outside evaluation, quality controls or accountability. While such entrepreneurship reduces costs, it is certainly not helping in maintaining any oversight or overall academic quality. It is also a very counter-productive trend as field schools that award credit units allow students to transfer such credits to their home institutions and save tuition costs there – not paying tuition for the transferred credits and graduating earlier. In theory and in practice, therefore, a no-credit field school is vastly more expensive to student than a program awarding credit units.

Figure 11: Percentage of archaeology field schools offering academic credit units (Data from the Twin Cairns Intelligence Unit)

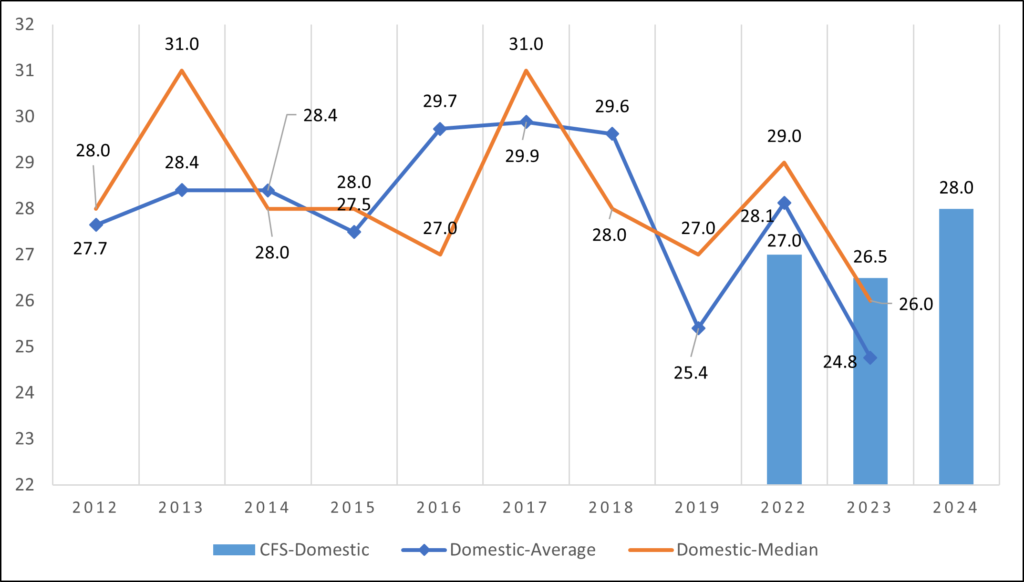

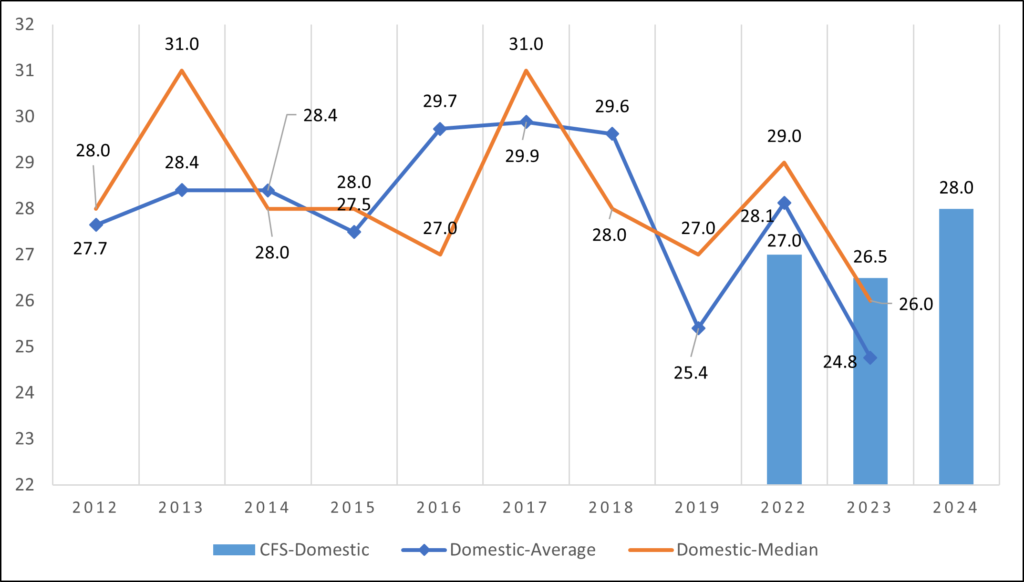

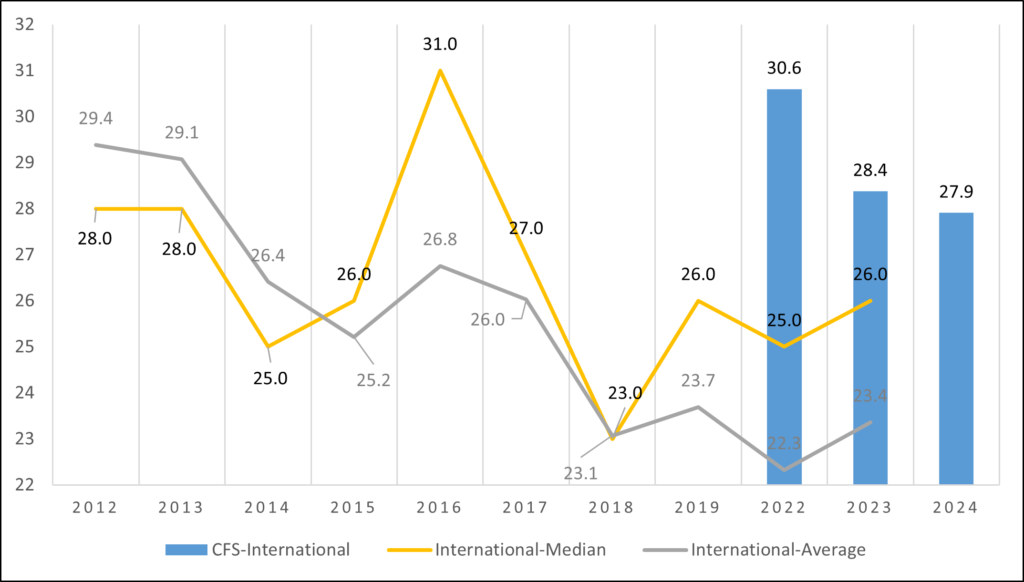

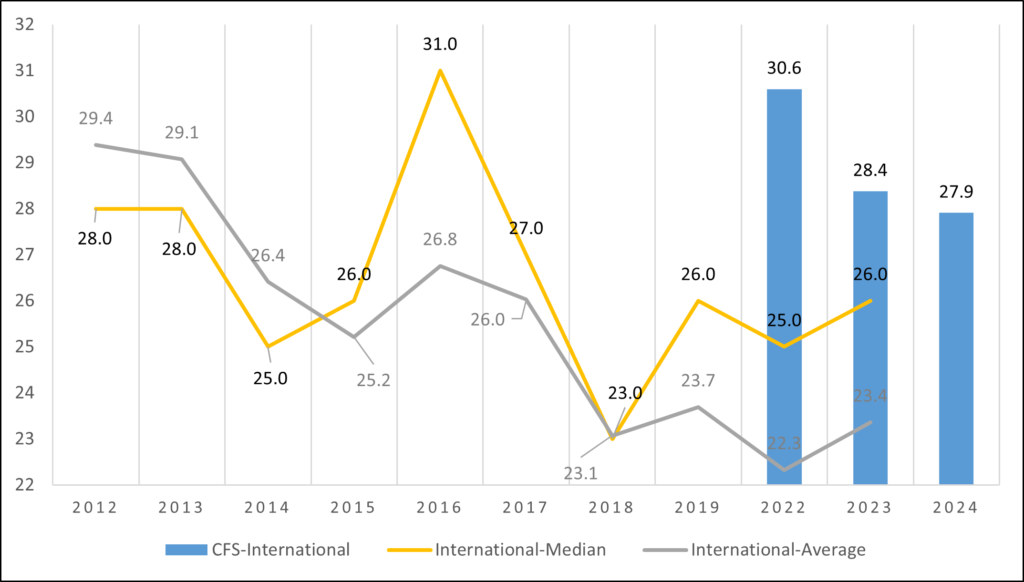

As the economic pressure to reduce field school costs builds, the average field school duration is declining as well (Fig 12-13). Very few field schools now offer more than four weeks in the field, and increasingly, program length – especially for international field schools – is trending towards a three week program (Fig 13).

Figure 12: Average length (days) of domestic archaeology field schools (Data from the Twin Cairns Intelligence Unit)

Figure 13: Average length (days) of international archaeology field schools (Data from the Twin Cairns Intelligence Unit)

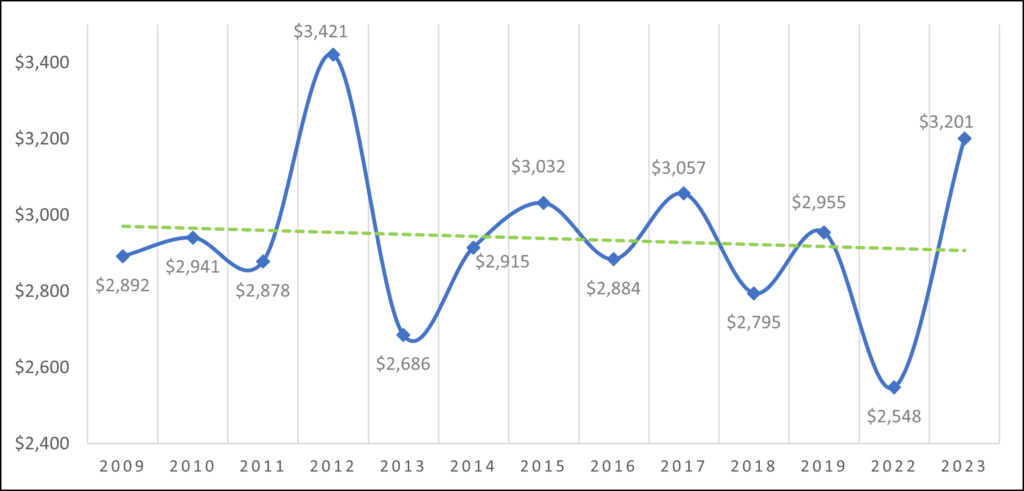

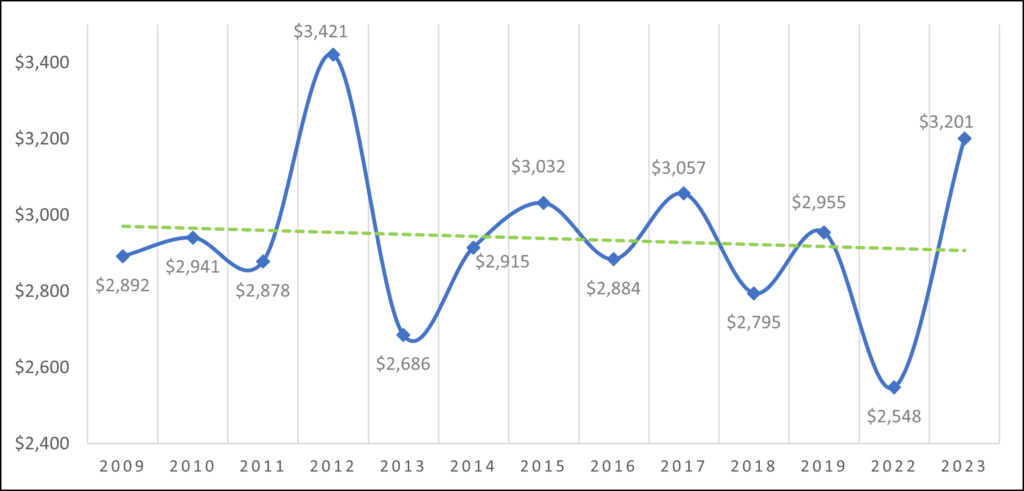

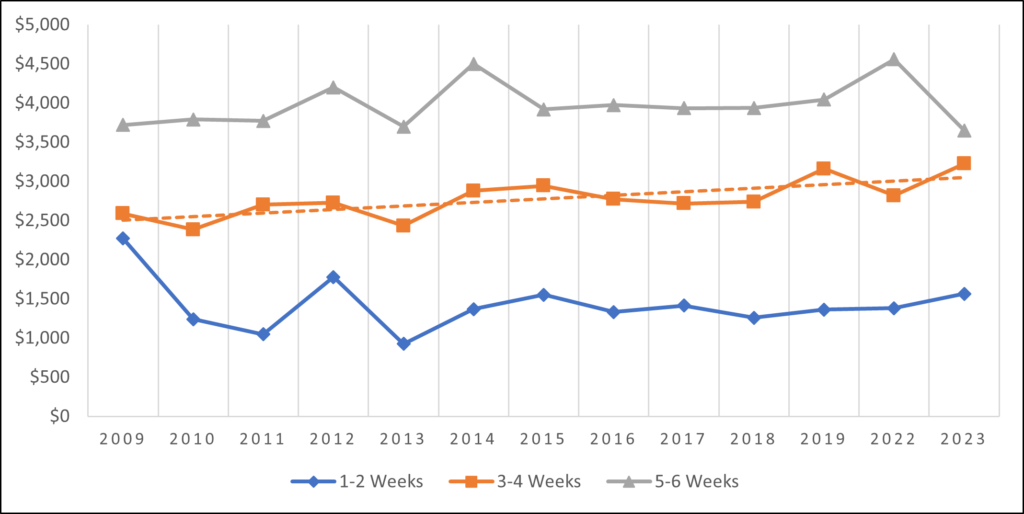

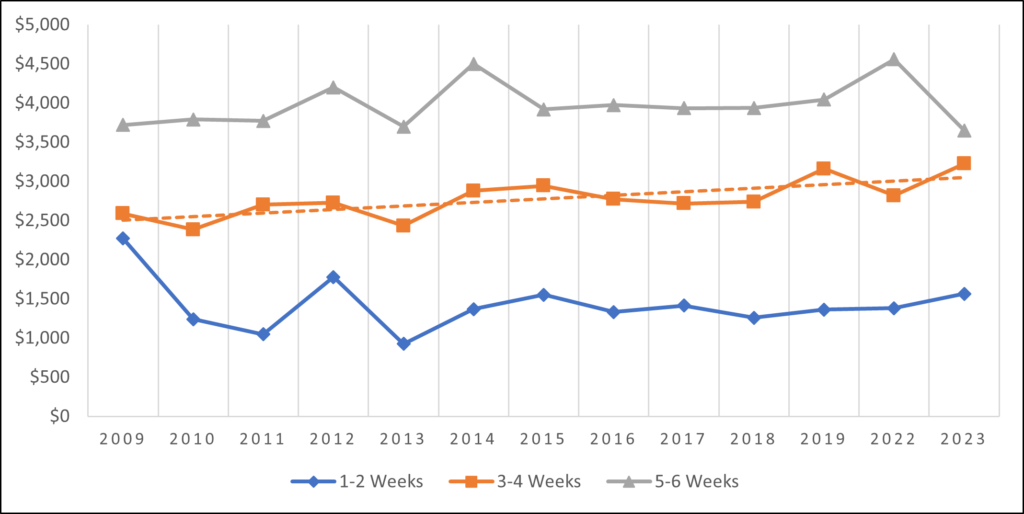

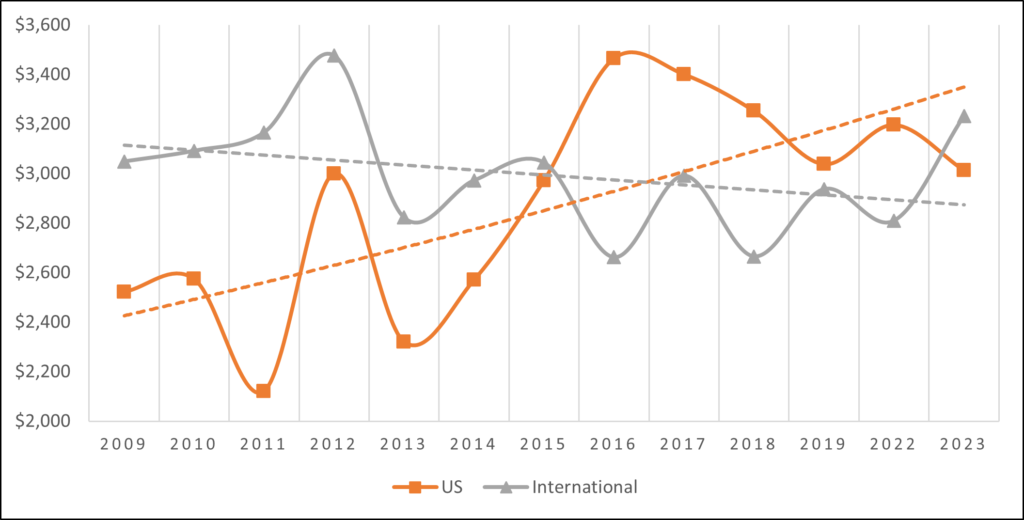

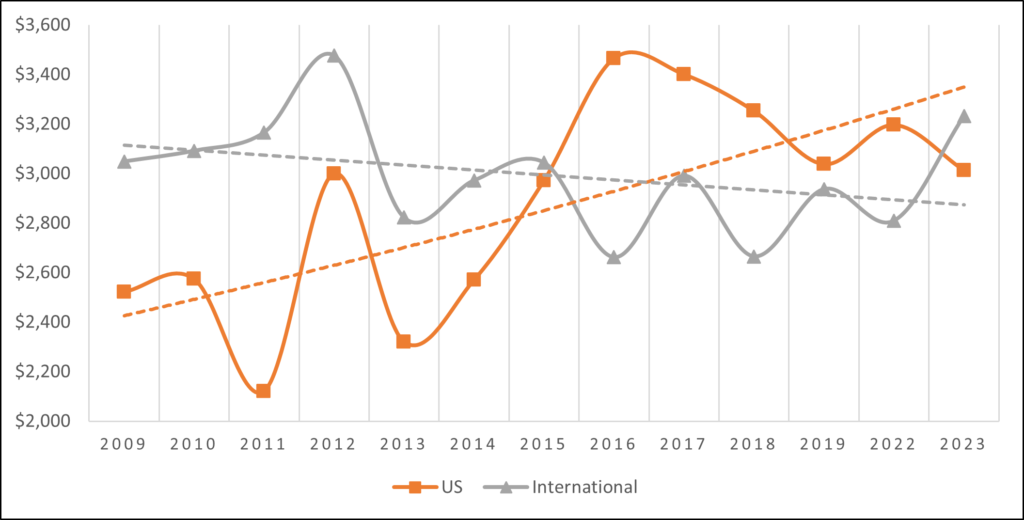

The average archaeology field school’s cost fluctuates tremendously (Fig 14). But the data becomes more stable and predictable when adding the field school length (by weeks) to the analysis. While short field schools (1-2 weeks) cost are fairly stable, and long field school (5-6 weeks) are also stable, the cost of the most popular field schools (3-4 weeks) is increasing (Fig 15). When comparing the cost of domestic with international field schools, the trend is quite clear. Since 2015, the cost of the average domestic field school was higher than that of an international one – with 2023 presenting a reverse anomaly (Fig 16).

Figure 14: Average archaeology field school tuition (Data from the Twin Cairns Intelligence Unit)

Figure 15: Average field school cost, by length (weeks) (Data from the Twin Cairns Intelligence Unit)

Figure 16: Average cost of domestic vs international field schools (Data from the Twin Cairns Intelligence Unit)

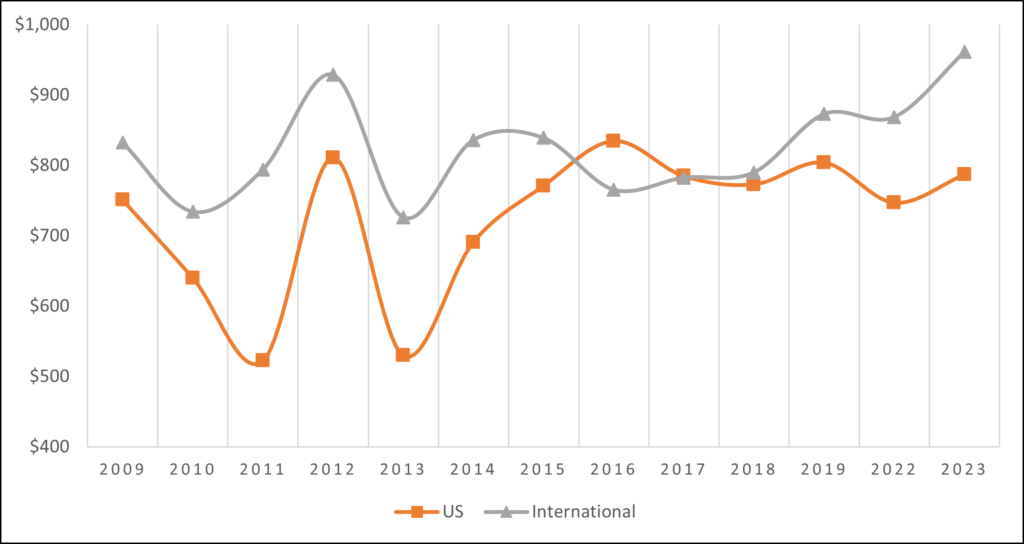

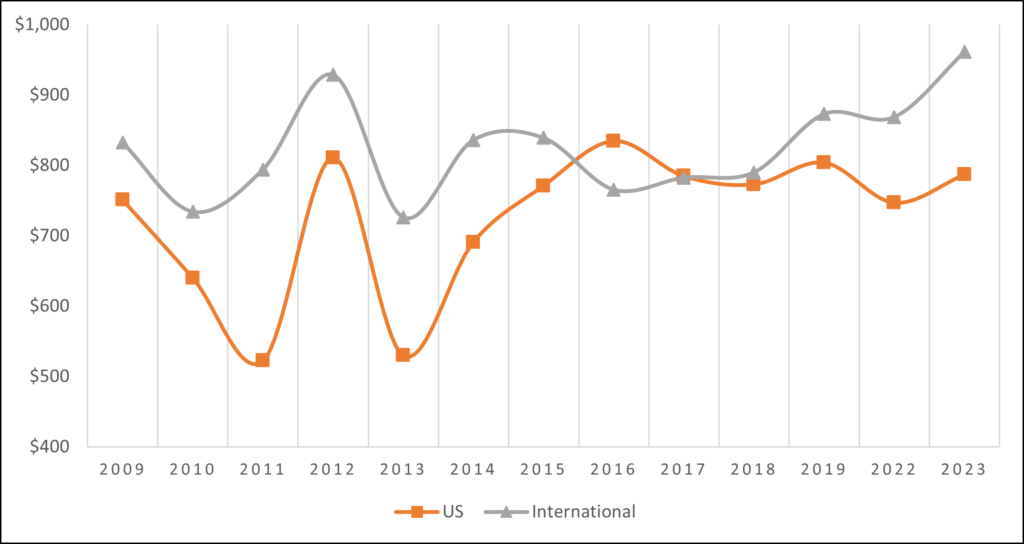

Because field schools are so diverse in their length, it is not easy to compare costs and understand what the trends are when observing total tuition cost only. One way to allow for comparison is to compare the cost per week of a field school. The cost of a week of domestic field school fluctuated dramatically between 2009-2014, and then stabilized somewhat in the $700-800 range (Fig. 17). The cost of one week of international field schools was less volatile in years past but jumped to $961 in 2023.

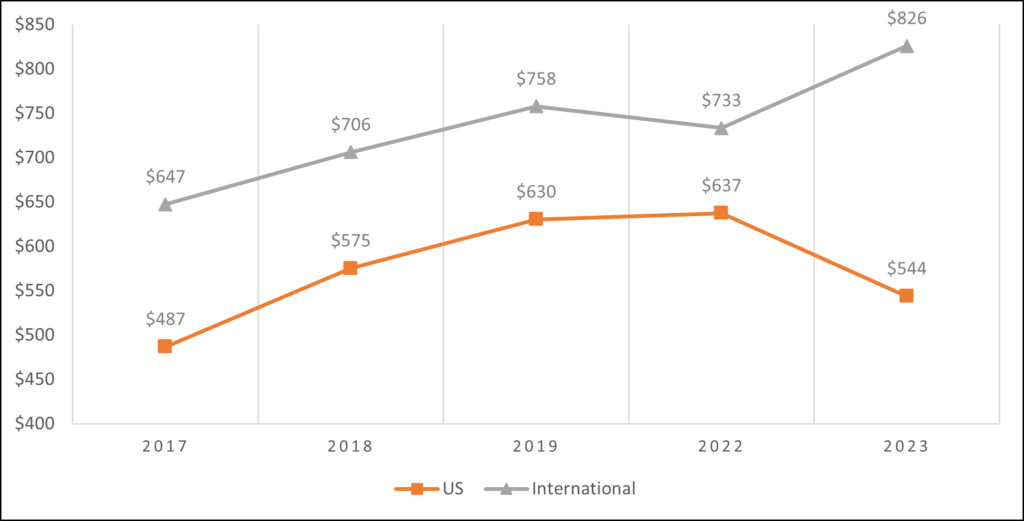

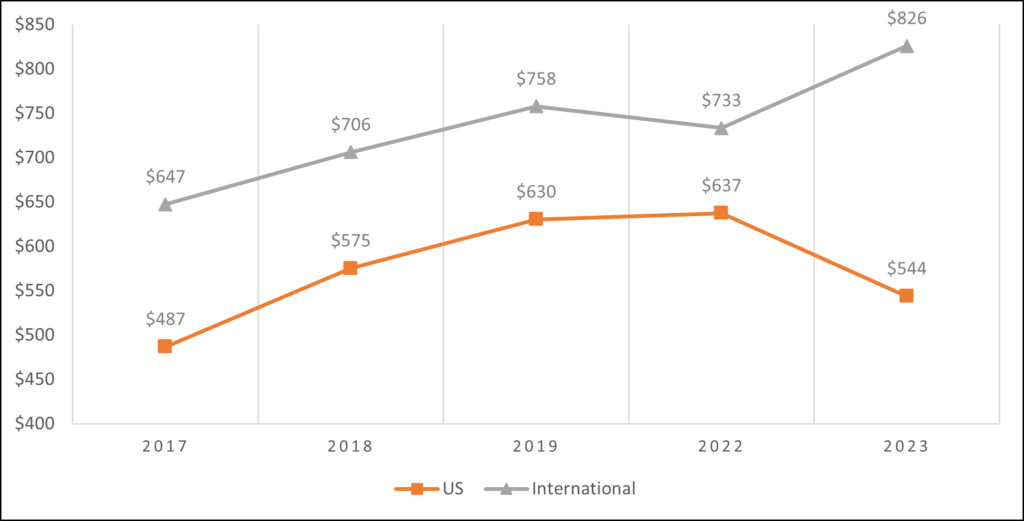

The only field schools that bring financial ROI to students are those awarding transferable academic credit units. Although less than half of all field schools are now awarding any number of credit units (Fig 11), it is useful to isolate those who do and examine the cost of a single credit unit. Such data was collected only from 2017 forward. The cost of a credit unit for domestic programs is significantly lower compared with international programs, suggesting that attending domestic programs brings the best ROI for students (Fig 18).

Figure 17: Average cost of one week of field school, domestic vs international programs (Data from the Twin Cairns Intelligence Unit)

Figure 18: Average cost of academic credit unit (adjusted to semester based credit unit), domestic vs international field schools (Data from the Twin Cairns Intelligence Unit)

Observations

For archaeology to thrive in the US for the next few decades, a major shift to CRM must take place. Yet we have a structural misalignment that makes such a shift hard to achieve. Universities, who traditionally train students for archaeology careers, have built-in promotion structure that is in serious conflict with CRM training. Faculty must publish to gain and remain in academic positions. They can do that primarily through excavations. Yet CRM requires training primarily in survey, and lots of discussions about legal compliance and consultation. Thes are not typically publication venues for academic archaeologists. Faculty self-interest, therefore, goes against the need to shift to CRM.

The organization that officially represents the interest of the CRM industry is the American Cultural Resources Association (ACRA). Of the estimated 1,600 CRM companies in the US, only 128 are listed as ACRA members (search conducted Jan 15, 2024). The organization is small, with only one full time employee and no permanent political advocacy specialist. ACRA has limited resources, represent the interest of less than 10% of companies in the sector, and at least thus far, took no initiative or invested any resources into supporting the shift towards CRM.

CRM companies are seeing a huge increase in revenue. In 2022, Jeffrey Altschul and Terry Klein calculated that revenue for the CRM sector will grow from $1.46B to $1.85B for each of the coming 10 years (Forecast for the US CRM Industry and Job Market, 2022–2031, The Archaeological Record Vol 10(4): 355-370). This projected 27% increase in revenue caught the attention of Wall Street. By Sep 2022, the Riverside company – an investment company specializing in the smaller end of the middle market – completed its investment in PaleoWest, and went on an acquisition spree. The result is Chronicle Heritage, now one of the largest CRM companies in the US. All this is relevant as the actions of Riverside and Chronicle Heritage brought a wave of consolidation to the sector, and most companies are focusing on either protecting their turf or selling to larger players. Whatever revenue CRM companies are generating, these are invested in increasing value, not into training or addressing structural shifts that impact the long term health of the sector. So CRM companies, acting in their own self interests at a time of unprecedented external financial investment, find it very challenging investing resources, energy or time in medium or long term goals for a healthy sector.

The Society for American Archaeology (SAA) recognized the shift towards CRM and is trying to take leadership – both in public statements and by nominating two CRM professionals to run for the SAA presidency – Donn Grenda from Statistical Research Inc and Christopher Dore from Heritage Business International. But the SAA ship is big and heavy and does not turn easily. With many SAA members at academic institutions, it is not clear that the SAA would invest more than token resources in CRM.

Everyone seems to wait for the government to act. In a recent publication, the presidents of the SAA, RPA, ACRA and the AAA Archaeology Division (SAA Archaeological Record 2023 Vol 23(3):3) jointly wrote: ”Many of our organizations are working actively on these matters, and they will be addressed extensively at the planned Airlie House 2.0 workshop”. While the federal government has considerable resources and can legislate mandates or change regulations, the current political reality in the U.S. is that the government will not likely take the lead.

Governments at all levels are, or soon will be, under tremendous pressure to eliminate cultural heritage preservation mandates if the CRM sector cannot deliver completed projects in timely fashion and at reasonable prices. Will market forces alone impact the direction of archaeology and produce the necessary training for CRM professionals at large enough scale? Not clear. We are at an infliction point for archaeology. How we, as a community, move forward will have a tremendous impact on the future of our national heritage and the laws and regulations that govern its preservation. Leadership is important, but so are grassroot efforts by individuals and organizations across the land. Action is required today. The past can ill afford to wait….

This is a very valuable paper. It should be widely circulated. The CRM staffing crisis relates to, as Altschul and Klein said, the obsolete structure of academic programs, and also the severe cuts to non-STEM programs and courses as the revived Cold War heats up. SUGGESTED TO HELP: create programs for technicians in archaeology in community and technical colleges. These schools, so valuable for communities and increasingly wanted instead of four-year colleges, are being drastically cut except for STEM courses. Most of fieldwork can be carried out by persons trained directly in field skills, with a basic level of general anthropology to help fieldworkers deal with collaborations with communities and descendants. This could be a two-year program and students could live at home or nearby. Altschul and Klein suggested more M.A. programs but those already would be too expensive and too long to produce the number of fieldworkers needed. ANOTHER area to pursue is to get CRM-prep programs into Engineering schools. Many of the early CRM archaeologists worked within large engineering companies, many still do. Engineering schools are booming and some are adding anthropology to their social sciences-humanities programs. A degree program for CRM personnel would not be difficult to build in Engineering schools. The best contact for pursuing this would be Engineering’s accreditation body: The key organization is ABET (Accreditation Board for Engineering and Technology, Inc. : https://nam02.safelinks.protection.outlook.com/?url=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.abet.org%2F&data=05%7C02%7Cakehoe%40uwm.edu%7Cbbd7c8bb3aa144625add08dc17446287%7C0bca7ac3fcb64efd89eb6de97603cf21%7C0%7C0%7C638410829700728128%7CUnknown%7CTWFpbGZsb3d8eyJWIjoiMC4wLjAwMDAiLCJQIjoiV2luMzIiLCJBTiI6Ik1haWwiLCJXVCI6Mn0%3D%7C3000%7C%7C%7C&sdata=d%2BAW0M%2BJBdI14i%2BcPK3guB7F1GXp%2BDa6umCCTn%2FxMGo%3D&reserved=0.

Ran Boytner is working on publishing a longer, more detailed version. This is a summary of that paper. We believe that it is best to have this data out now, even before the academic journal review process that will take months to get the manuscript published.